A New Church to Mixed-Use Development in Arlington

And what it’s taught me about the potential for faith-based redevelopments

Arlingtonians may have recently noticed a new apartment building just across the street from the Ballston Metro station. It’s almost ready to start leasing, and it’s a particularly special building to me, as it’s the first faith-based redevelopment project I’ve worked on in my career. Originally the site of the Central United Methodist Church (CUMC) of Ballston, the new project will hold a modernized church sanctuary for CUMC, along with 144 units of income-restricted housing and an 80+ seat Kinhaven childcare center. Like many church redevelopments, this project represents a win-win for affordable housing development and the church, who used the sale proceeds (in this case, long-range ground lease payment) to construct a new, modern facility while also contributing to their mission of housing others. Faith-based redevelopments, like office conversions, have been getting a lot of buzz lately. And for good reason! Many church sites are underutilized and could make a real dent in needed housing production, especially in high-demand places. In this post, I look back at the CUMC project and the lessons it holds.

Project Origins

CUMC’s motivation to redevelop was twofold: 1) raise money to modernize the church sanctuary and spaces and 2) maximize the church mission by providing housing to neighbors in need. After over a century of service at this location, the church was committed to staying on site long-term to continue its many services to the community, including hosting a preschool facility and serving weekly meals to those in need. Planning for the redevelopment began in earnest in 2015, when the congregation voted to redevelop their nearly 100-year-old sanctuary into housing.

Located at 4201 Fairfax Drive, the site is just across the street from the Ballston Metro station, which has two Metrorail lines and bus bays with over a dozen bus lines. For those unfamiliar with Arlington, the Ballston neighborhood is the westernmost terminus of the Rosslyn-Ballston metro corridor, which has been home to most of the county’s population growth and mixed-use development for the past several decades. The site lies across the street from what is now the densest census tract in the DC region and is within walking distance to hundreds of restaurants, grocery stores, and schools in the neighborhood. Fortunately, the county general land use plan designated the site as “high-medium” residential mixed use, keeping with the county’s long held policy of allowing growth and development around its transit corridors. This facilitated a speedy 8-month rezoning process from commercial to residential development in 2016-2017. Also in 2017, the county adopted new off-street parking guidelines new metro stations, which allowed the project to reduce its underground parking to one level (53 spaces total), saving the project about $3M in costs which was reinvested into lowering rents.

Design and Building Uses

Like many mixed-use redevelopments, the biggest challenge for the project design was fitting a lot of stuff into a tight site -- a new CUMC church sanctuary, a childcare space for about 86 kids, and 144 new apartments. But with increased density, an increased building footprint, and creative uses of courtyards, the team has been able to accommodate all parties. The first floor plan below illustrates how these diverse uses will fit together when everyone moves in.

Meanwhile, the upper floors generally follow a U-shape with a central courtyard. This central courtyard will serve as outdoor space for the multiple tenants, with 2nd floor access to a play area for the daycare in addition to a 3rd floor resident terrace.

The increased density in the new project has allowed a diverse mix of childcare, community activities, and residential living to co-exist, breathing new life to this corner of Ballston. And although the old church is gone, the new sanctuary offers a bright, modernized space for the congregation to worship. CUMC was even able to preserve several beautiful stain glass windows from the old church, a poignant reminder that we can build for the future without forgetting the past.

Project Costs and Financing

The total development costs for the project totaled about $84M, of which about $70M is attributable to the residential portion of the building. This comes out to about $491,332/unit, which, while quite costly pre-pandemic, is closer to the norm post-COVID. To pay for these costs while still offering rents at 60% AMI or below, the project used a variety of government subsidies, including Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) equity and a low-interest loan from Arlington County.

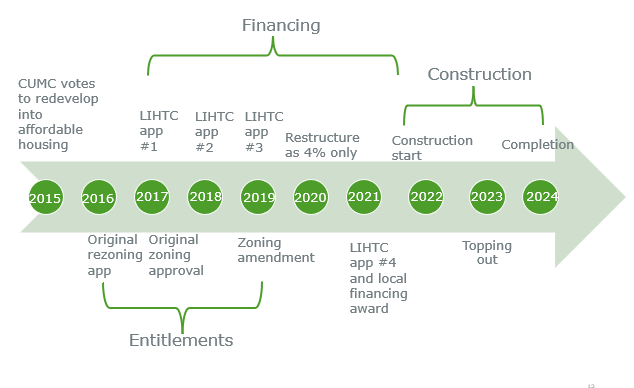

After being originally designed in 2017 as mixed-income housing with 119 units, the project failed several attempts to win LIHTC financing in 2017, 2018 and 2019. After this, the project was finally redesigned as a 100% income-restricted affordable housing development with 144 units financed with 4% LIHTC. Because 4% LIHTC raise less investor equity than 9% credits, the project team also redesigned the building to create more 1-bedroom units to increase operating revenue from rents and thus, the amount of supportable debt on the project.

The several failed tax credit applications and project redesigns also contributed to larger-than-normal soft costs through extra architectural and legal work. With that said, Arlington County deserves enormous credit for stepping up to make the project pencil by increasing their loan contribution after the switch to 4%-only financing.

Some of the extra legal work needed in this case was to specify distinct condominium units for the residential and church/daycare spaces. Once these were set, the development team could more easily isolate accounting and cost divisions for each side of the project. One tricky piece of making these business deals work is negotiating a fair split of shared building costs, such as garage spaces, foundation work, and site work between the various spaces. This takes time and careful discussion, but after this was done , the church/daycare were able to pay for their costs through the money they received from the sale price (in this case, in the form of a capitalized ground lease payment) from the residential side plus a little extra fundraising.

Project Construction

Project construction started in December 2021 and is scheduled to complete by March 2024. The building consists of 5 levels of wood frame construction above 3 levels of concrete, while the exterior cladding mainly consists of brick and fiber cement. There were a few notable complexities to the project, some of which are common for most urban infill projects. First, the construction required extensive utility relocation with neighboring retail and a Wells Fargo bank close by. Second, due to its proximity to the metro tunnel (what WMATA terms a “zone of influence”) under Fairfax Drive, the project also had to undergo a special WMATA permit review and ongoing monitoring to ensure there would be no structural impact on the tunnel. The project also required regularly reserving a lane of traffic on Fairfax Drive and Stafford Street for utility installation and site work. Davis Construction, the general contractor on the project, handled these complex issues with aplomb.

Because of the proximity of all the uses in a single building, Davis Construction served as the single general contractor on the project responsible for both the residential and church/daycare exteriors and interiors. At the end of construction, the developer will turn the keys (hence, the origin of the term “turn-key” development) of the church/childcare space over to the church.

Project Timeline and Final Thoughts

Church redevelopments are complex work but can be a rare opportunity to build affordable housing in urban locations with scarce land. After 3 failed tax credit applications and several project redesigns, it has taken about 9 years in total for this project to come to fruition. And through all its struggles, the project accomplished a lot – 144 units of subsidized affordable housing with a 26,000 square foot church and new daycare space for 80+ kids across from a bustling Ballston metro station. Although I hope I’m not boring readers too much with the details, that’s kind of my point! These projects are seriously hard work, and if policymakers want to see more of them happen, it’s critical to focus on how to make them easier. With that in mind, a few final thoughts:

Churches can help provide housing, but only if we let them. This sounds obvious, but our zoning policies don’t act like it. For many churches struggling to survive, zoning makes it outright illegal or extremely burdensome to build additional housing. And as you can see from the case of CUMC, these projects have enough complications without the additional stress and costs from zoning barriers. For that reason, California recently passed SB 4 that allows a minimum amount of housing to be developed by-right on all land owned by faith-based organizations statewide. A recent Terner Center report shows that there are over 47,000 acres of such land in California, presumably enough to build hundreds of thousands of units. A similar bill proposed in the Virginia legislature has unfortunately indefinitely continued until next year.

Faith-based redevelopments are just as much about anti-displacement as they are about building affordable housing. In the case of many churches, the choice is between redevelopment with housing or outright displacement to a lower-cost area or space. It’s critically important for our communities to do what we can to offer them a chance to remain in place. This is especially true given the large number of churches that host childcare centers, which are in critically short supply in Arlington.

Faith institutions want to do good, not talk about zoning. Churches who want to build affordable housing are putting their faith into action by using their land to building housing for people in need. But the unfortunate reality with our current system of zoning and development is that it forces them to spend thousands of dollars and years of their time on legal counsel and public hearings before we let them do those good things. It’s a policy failure that we expect church congregations to become legal or zoning experts to build the housing for those in need. So, to the first point above, let’s make it legal for them to build through statewide reforms.

An honest, shared vision is critical. Change is difficult, but it’s important to have honest introspection and clear communication with these projects. For many churches, the reality is a need to downsize to a smaller, modernized space. Accepting this reality certainly makes developments more feasible. And even if downsizing is not needed, establishing clear priorities from the beginning can help decide between the inevitable tradeoffs that come throughout the development process. In CUMC’s case, they had full visioning process (explained in more depth here) at the outset of the project to identify congregational priorities.