How much does it cost to build (subsidized) affordable housing?

A rough guide based on DC-area projects

Zoning reform, simply making it legal to build more housing in more places, is a necessary part of digging ourselves out of our historic housing shortage. But lowering development costs to make it financially feasible to build more housing is perhaps an equally important part of the solution. The Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley has a wonderful series on the costs of building housing in California. In this spirit, I thought I’d share my experience about development costs working as a nonprofit housing developer in the DC area.

The charts below present some average costs from a sample of 10 affordable housing projects in the DC area. These projects were all built or started construction sometime between 2013 and 2025.[1] Before delving in, a few caveats. The sample involves subsidized affordable housing produced by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Although there are some cost differences between this and market-rate housing, my experience is that these differences tend to cancel each other out. On the one hand, while market-rate apartments usually have more costly interior finishes and common-area amenities, LIHTC housing must deal with additional financing complexities or costly government requirements that market-rate apartments don’t. Second, the sample includes only mid-to-high-rise apartment projects recently built (between 2013-2025) in the DC metropolitan area, a high-cost market that is not representative of the whole country. Third, these projects all come from a single developer, True Ground Housing Partners, where I currently work. Finally, for the sake of comparability, the projects I chose for this exercise are all ground-up new construction buildings with underground parking, a common feature for new buildings in the inner-ring suburbs of DC.

So while this sample isn’t representative of new multifamily housing overall, it’s a good data point, especially given that LIHTC developments often makes up a sizeable amount (25% by some estimates) of multifamily housing starts in any given year. High-cost markets like DC area are also where there are the most acute housing supply shortages. These costs can offer some potential areas for cost reform so we can more efficiently use scarce subsidies to produce affordable housing. That means more units per dollar spent! This is especially important given increasingly strained budgets at the federal, state, and local levels.

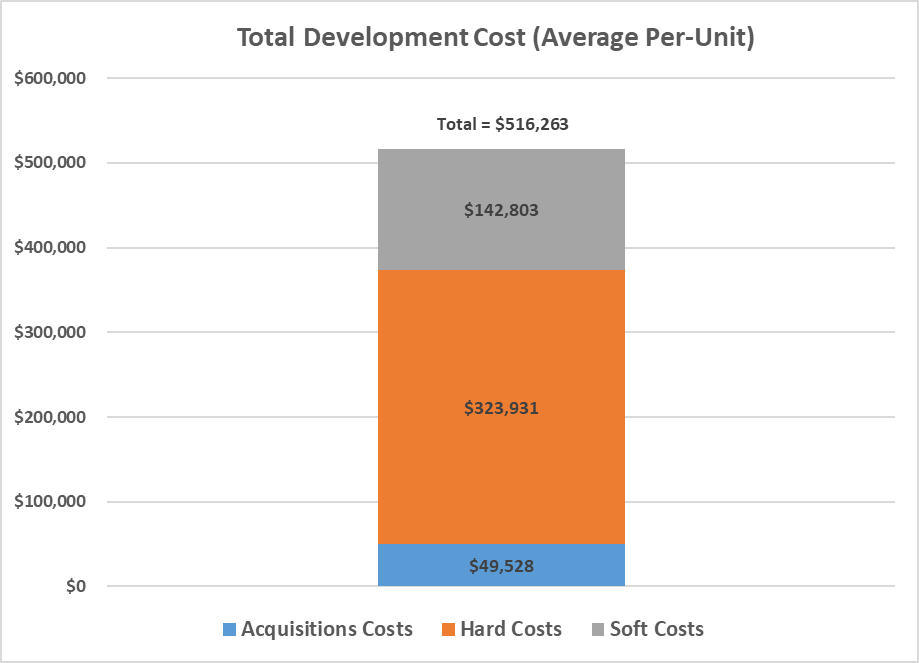

Total Development Costs

On average, it costs a little over half a million dollars ($516,263) to build one unit of affordable housing from this sample of projects. This total is composed of three broad subcategories of cost:

Hard Costs ($323,931): The amount paid to the general contractor for the labor and materials to construct the building.

Soft Costs ($142,803): A broad set of costs related to designing, permitting, marketing, and financing the building.

Acquisition Costs ($49,528): The cost to acquire (in most cases, purchase outright, in some cases ground-lease) the land for building.

Acquisition costs are self-explanatory, but let’s explore the hard and soft cost categories in more detail.

Hard Costs

Hard costs, the costs required to construct the building, are the largest driver of development costs. Buildings are extremely complex and require the work of hundreds of different skilled trades all under the coordination of a general contractor. The industry does have a standard set of costs, known as CSI divisions, which divide costs into a set of 50 universally-accepted categories. For the sake of this simplicity, I’ve chosen a different, broader set of subcategories in the chart above:

Base Building ($222,246): The cost of materials and labor for the subcontractors responsible for doing the construction work. This includes many different trades, such as foundation work, framing, concrete, masonry, metals, wood & plastics, plumbing, etc.

Garage ($39,628): The costs of building an underground parking garage in the building (i.e. additional excavation and concrete). It’s not always typical to track this cost separately, but the projects in my sample here track this due to Virginia Housing tax credit rules.

Site Work ($18,662): The costs of preparing the site for pre-and-post construction. This includes excavation, building new or relocating existing utility lines, physically moving dirt to prepare for the building foundations, new pavement around the building, and landscaping.

General Conditions + Profit ($34,220): Overhead and profit for the general contractor, who is contracted to lead the construction work. The general contractor coordinates the work of all the subcontractors on site and communicates any issues or progress updates with the owner and architects throughout construction.

Other ($9,175): Miscellaneous other fees, such as commercial liability insurance fees, taxes, and bond fees paid by the general contractor.

Together, hard costs make up about 60% of total development costs, and so any significant effort make development cheaper at scale will have to reckon with how to lower these costs. One obvious local policy fix that can help is removing minimum parking requirements. Over 10% of the hard costs above are for building underground parking. This usually always translates into seven-figures of additional cost that can make or break a development project. I have personally worked on several projects saved by lowering parking minimums in Arlington. Nationally, dozens of localities (e.g. Minneapolis) have eliminated parking to the effect of sharp increases in housing production.

On a federal level, wage requirements attached to federal funding can also dramatically raise costs. Although I haven’t broken them out separately, two of the projects in the sample above include federal funding that requires prevailing wage rates per the Davis-Bacon Act. These projects have about 30% higher base building costs than the rest of the sample. Although these wage requirements might be a worthwhile labor policy goal, the tradeoff in reduced affordable housing production is very real.

Beyond this, reducing hard costs is hard, complicated work. Construction costs have consistently outpaced inflation for the past 100 years, and there’s some evidence that stagnating labor productivity is a major cause. Reducing these costs will take the hard work of both increased hiring in the construction sector combined with innovation of building practices. Suffice it to say that recent calls to restrict immigration and increase tariffs will only make these costs worse. Personally, I’m also excited about the potential of low-hanging fruit from building code reforms (e.g. elevator cost reform) that lower costs by bringing us more up to date with international best practices.

Soft Costs

Soft costs are the “everything-else-other-than-construction” costs. The wide variety of costs here reflect the complexity of real estate development and the range of subject-matter specialists involved. In the chart above, I grouped soft costs into several broad sub-categories:

Architecture, Engineering, & Inspections ($25,394): This category includes architecture costs for designing the building and supervising the design during construction. It also includes several engineering disciplines – civil, structural, mechanical – involved in the design. As a developer, True Ground doesn’t have in-house design or construction expertise, so we typically hire a third-party construction manager to review materials from the design team, which is included here. Also included here are regular inspections of materials during construction. Finally, I included the cost of purchasing furniture for the common areas of the building (typically a few thousand dollars per unit) here.

Legal, Accounting, & Insurance ($9,597): This includes legal fees for negotiating all of the transaction documents (e.g. purchase and sale contract, loan documents, etc.). It also includes accounting fees for preparing cost certifications for tax documents. Third, it includes insurance covering the building materials (called builder’s risk insurance) as well as general liability insurance for during the construction process.

Permitting, Proffers, & Taxes ($18,555): This includes building permit review fees from the local building department. It also includes proffer requirements, additional fees added by the locality through the development review process to mitigate neighborhood impacts. These can vary widely, from new streetlights and bike racks to replanting trees and even public art contributions. I am also including permitting-related consultant fees, such as traffic or environmental impact consultants (often required to complete studies during zoning approval) in this category. Finally, this category includes property taxes due during construction.

Marketing & Lease up Costs ($7,669): This includes the costs of appraisals and market studies needed for tax credit or financing applications. It also includes costs for marketing the building during lease-up. Finally, some projects include project betterments, such additional maintenance materials or backup supplies, at the end of a project when there are excess funds. I’ve included those here.

Developer Fee ($37,144): The fee paid to the developer to manage the project. This helps pay dozens of staff (development project managers, asset managers, accountants, etc.) that touch the project over its lifecycle. It also gets recycled to fund feasibility studies and design for future affordable housing projects (what we call “predevelopment funding”). It is standard practice that at least half of this fee be “deferred” until after construction is completed and paid back annually on a contingent cash flow basis.

Financing Fees ($28,611): Fees paid to the lenders and investors who finance the project for their review and underwriting. Each project typically has between 5-10 separate sources of financing and they each have their own review process. This category also includes the interest paid on the construction loans during the building process.

Reserves ($15,834): It is standard practice to fund up-front reserves for operating, lease-up, and replacement expenses at the time a building opens. These reserves help keep the building running in case there are leasing issues and help fund occasional maintenance over time.

There are so many components to soft costs that it’s hard to pinpoint any one category as a silver bullet for reducing overall costs. But it’s worth mentioning a few general drivers of cost across multiple categories above.

The first is financing complexity. Because of our fragmented system of funding affordable housing, each project typically has 5-10 funding sources for each project. This typically includes a combination of private investment from a LIHTC investor, permanent loans and construction loans from a private banks, and additional loans low-interest loans from state and local governments. Each one of these financing sources comes with its own set of conditions, timing, and legal documents that may or may not overlap nicely with the others. Coordinating these different sources to fund a project takes enormous amounts of staff time and legal review, not to mention separate financing fees for every source. Putting a precise estimate on these added costs is difficult, but research from California by the Terner Center suggests it could be as high as $6,500/unit for each additional funding source. One way to reduce these costs is for state, local, and private lenders coordinate program requirements and timing in advance.

A second driver of costs is zoning uncertainty, something that is not unique to affordable housing. Like most American cities, localities in the DC area ban apartment-building on most of their land area. And where it is legal to build, it usually requires extensive zoning review and public hearings that can take anywhere from months to years to complete. This review process, known as “discretionary review”, adds significant design, legal, and staff costs by requiring multiple design changes. Zoning laws are often extremely complex and require a specialized land use counsel to guide developers through the zoning approval process. Zoning more land for apartments “by right” with simplified, standardized rules, could help reduce costs substantially.

That’s it for now! Hopefully these charts can give you a helpful mental map of the cost components of affordable housing and their rough size. To conclude, below is a table with all the cost categories mentioned above. And to all pro-housing allies, consider raising cost reform in your next advocacy meeting.

Total Development Costs – Full Table

[1] Eight of these projects are in Arlington County, VA, one is in Fairfax County, VA, and one is in Washington, DC. The projects vary in size from 93 to 516 units. Most of the projects are either concrete framing or a concrete podium with wood-framing. Various manual assumptions were made in creating standardized cost categories across projects.

This is really helpful to know! Policies like the Maryland's Housing for Jobs bill would help reduce that uncertainty from the discretionary review process: https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/sb0430?ys=2025RS

Fantastic article. Much of writing on housing affordability focuses on zoning and costs in the abstract, and you get a different picture when taking a closer look at the actual data. Patrick McAnaney wrote a similar breakdown for GGWash which focuses more on different financing sources (equity vs debt): https://ggwash.org/view/92306/why-affordable-housing-cant-pay-for-itself

I have a few questions I’d be interested to know your thoughts on:

1. I’m not sure which category(s) of costs zoning battles it would fall into here, but based on the breakdown I’m having trouble seeing where you would get cost savings from loosening zoning restriction/building by right. Not sure if that’s just because of the type of projects you work on?

2. There are a number of substantial line items (developer/contractor profit, loan interest, fees) which seem necessary for a well functioning private market, but could those be eliminated or reduced in the case of public housing? I also find it interesting the back and forth flow of money between developers and government in the form of fees and subsidies.

3. I’m curious how much you would say the size of these projects adds vs reduces costs. It seems like complexity plays a big part in driving up especially the soft costs, and on a per unit basis I’m wondering how the cost compares to a much smaller scale project like an ADU.